Lophelia pertusa, the only species in the genus Lophelia,[2][3] is a cold-water coral which grows in the deep waters throughout the North Atlantic ocean, as well as parts of the Caribbean Sea andAlboran Sea.[4] L. pertusa reefs are home to a diverse community, however the species is extremely slow growing and may be harmed by destructive fishing practices, or oil exploration and extraction.

Lophelia pertusa is a reef building, deep water coral, which is unusual for its lack of zooxanthellae– the symbiotic algae which lives inside most tropical reef building corals. Lophelia lives between 80 metres (260 ft) and over 3,000 metres (9,800 ft) depth, but most commonly at depths of 200–1,000 metres (660–3,300 ft), where there is no sunlight, and a temperature range from about 12–4 °C (54–39 °F).

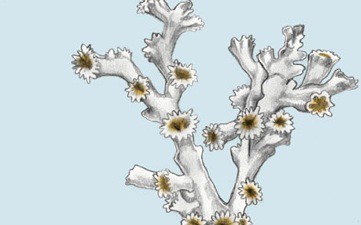

As a coral, it represents a colonial organism, which consists of many individuals. New polyps live and build upon the calcium carbonate skeletal remains of previous generations. Living coral ranges in colour from white to orange-red. Unlike most tropical corals, the polyps are not interconnected by living tissue. Radiocarbon dating indicates that some Lophelia reefs in the waters off North Carolina may be 40,000 years old, with individual living coral bushes as much as 1,000 yrs old.

The coral reproduces by budding off new polyps and by producing free-living planktonic larvae which float in the water until they find a suitable surface to attach to and grow on.

Lophelia reefs can grow to 35 metres (115 ft) high, be hundreds of metres wide, and the largest recorded reef measures 13 kilometres (8.1 mi) off the Lofoten Islands, Norway. When this is seen in terms of a growth rate of around 1 mm per year, the great age of these reefs becomes apparent.

Polyps at the end of branches feed by extending their tentaclesand straining plankton from the seawater. The spring bloom ofphytoplankton and subsequent zooplankton blooms, provide the main source of nutrient input to the deep sea. This rain of dead plankton is visible on photographs of the seabed and stimulates a seasonal cycle of growth and reproduction in Lophelia. This cycle is recorded in patterns of growth, and can be studied to investigate climatic variation in the recent past.

(From Wikipedia, May 31st, 2012)