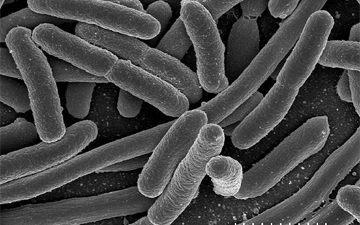

Escherichia coli (commonly abbreviated E. coli; pronounced /ˌɛʃɨˈrɪkiə ˈkoʊlaɪ/, named after Theodor Escherich) is a Gram negative rod-shaped bacterium that is commonly found in the lower intestine of warm-blooded organisms (endotherms). Most E. coli strains are harmless, but some, such as serotype O157:H7, can cause serious food poisoning in humans, and are occasionally responsible for product recalls.[1][2] The harmless strains are part of the normal flora of the gut, and can benefit their hosts by producing vitamin K2,[3] and by preventing the establishment of pathogenic bacteria within the intestine.[4][5]

E. coli are not always confined to the intestine, and their ability to survive for brief periods outside the body makes them an ideal indicator organism to test environmental samples for fecal contamination.[6][7] The bacteria can also be grown easily and its genetics are comparatively simple and easily-manipulated or duplicated through a process of metagenics, making it one of the best-studied prokaryotic model organisms, and an important species in biotechnology and microbiology.

E. coli was discovered by German pediatrician and bacteriologist Theodor Escherich in 1885,[6] and is now classified as part of the Enterobacteriaceae family of gamma-proteobacteria.[8]

E. coli is Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic and non-sporulating. Cells are typically rod-shaped and are about 2 micrometres (μm) long and 0.5 μm in diameter, with a cell volume of 0.6 – 0.7 μm3.[11] It can live on a wide variety of substrates. E. coli uses mixed-acid fermentation in anaerobic conditions, producing lactate, succinate, ethanol, acetate and carbon dioxide. Since many pathways in mixed-acid fermentation produce hydrogen gas, these pathways require the levels of hydrogen to be low, as is the case when E. coli lives together with hydrogen-consuming organisms such as methanogens or sulfate-reducing bacteria.[12]

Optimal growth of E. coli occurs at 37°C (98.6°F) but some laboratory strains can multiply at temperatures of up to 49°C (120.2°F).[13] Growth can be driven by aerobic or anaerobic respiration, using a large variety of redox pairs, including the oxidation of pyruvic acid, formic acid, hydrogen and amino acids, and the reduction of substrates such as oxygen, nitrate, dimethyl sulfoxide and trimethylamine N-oxide.[14]

Strains that possess flagella can swim and are motile. The flagella have a peritrichous arrangement.[15]

(From Wikipedia, May 24th, 2010)

– – –