The Nine-Banded Armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus), or the nine-banded long-nosed armadillo (and colloquially as the poor man’s pig orpoverty pig), is a species of armadillo found in North, Central, and South America, making it the most widespread of the armadillos.[2] Its ancestors originated in South America and remained there until 3 million years ago when the formation of the Isthmus of Panama allowed them to enter North America as part of the Great American Interchange. The nine-banded long-nosed armadillo is a solitary, mainly nocturnal animal, found in many kinds of habitats, from mature and secondary rainforests to grassland and dry scrub. It is an insectivorous animal, feeding chiefly on ants, termites, and other small invertebrates. The armadillo can jump 3–4 feet (91–120 cm) straight in the air if sufficiently frightened, making it a particular danger on roads.[3]

The Nine-Banded Armadillo evolved in a warm rainy environment and is still most commonly found in regions resembling its ancestral home. However, it is a very adaptable animal that can also be found in scrublands, open prairies, and tropical rainforests. They cannot thrive in particularly cold or dry environments, as their large surface area, which is not well insulated by fat, makes them especially susceptible to heat and water loss.[4]

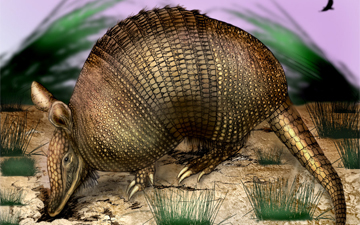

Nine-banded armadillos weigh 12–22 pounds (5.4–10.0 kg). Head and body length is 15–23 inches (38–58 cm), which combines with the 5–19 inches (13–48 cm) tail for a total length of 20–42 inches (51–110 cm). They stand 6–10 inches (15–25 cm) tall.[4] The outer shell is composed of ossified dermal scutes covered by non-overlapping, keratinized epidermal scales, which are connected by flexible bands of skin. This armor covers the back, sides, head, tail, and outside surfaces of the legs. The underside of the body and the inner surfaces of the legs have no armored protection. Instead, they are covered by tough skin and a layer of coarse hair. The vertebrae are specially modified to attach to thecarapace.[13] The claws on the middle toes of the forefeet are elongated for digging, though not to the same degree as those of the much larger Giant Armadillo of South America.[4] Their low metabolic rate and poor thermoregulation make them best suited for semi-tropical environments.[13] Unlike the South American three-banded armadillos, the nine-banded armadillo cannot roll itself into a ball. It is, however, capable of floating across rivers by inflating its intestines, or by sinking and running across riverbeds. The second is possible due to its ability to hold its breath for up to six minutes, an adaptation originally developed for allowing the animal to keep its snout submerged in soil for extended periods while foraging.[13] Although nine is the typical number of bands on the nine-banded armadillo, the actual number varies by geographic range.[13] Armadillos possess the teeth typical of all sloths, and anteaters. The teeth are all small peg-like molars with open roots and no enamel. Incisors do form in the embryos, but quickly degenerate and are usually absent by birth.[13]

(From Wikipedia, February 5th, 2011)

– – –

The tank-like Nine-banded Armadillo’s range has greatly expanded northward in the last 100 years. In the mid-1800s it was found only as far north as southern Texas; by the 1970s it lived in Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri and Tennessee; now it’s also on the East Coast. Armadillos are typically active at night or twilight. They shuffle along slowly, using their sense of smell to find food—mostly insects, and occasionally worms, snails, eggs, amphibians, and berries. They root and dig with their nose and powerful forefeet to unearth insects or build a burrow. They always give birth to identical, same-sex quadruplets that develop from a single fertilized egg. Only two mammals are known to get a disease called leprosy: humans and armadillos. This has made armadillos important in medical research.

Adaptation: The hips and the neck vertebrae of the nine-banded armadillo,Dasypus novemcinctus, include several bones that are fused in order to make the spine and back relatively rigid, as an adaptation to digging. Much like a mole, the skull is compact and relatively flat, which also makes it a useful tool for moving dirt.

(From Smithsonian NMNH via EOL)

– – –